A Long Way from Home. Melbourne, Victoria: Penguin Random House Australia, 2017.

A Long Way from Home. Melbourne, Victoria: Penguin Random House Australia, 2017.

Ostensibly this novel’s about Titch and Irene Bobs driving an FJ Holden around Australia in the 1954 Redex Trial. They’d have been lost without their navigator, Willie Bachhuber. Nowadays, Australians tow a caravan around the coast. I drove a campervan.

Titch and Irene dined at Doyles on Watson’s Bay, Sydney. I did too (and expect Peter Carey was taken there as a youth).

Matthew Flinders named Mount Larcom in August 1802 but was unable to reconcile his nautical observation with Captain Cook’s. I was unable to see eye-to-eye with the proprietor of the Mount Larcom cafe. Somewhere in the vicinity, Willie Bachhuber had his first conscious encounter with Aborigines, one of whom took a more than passing interest in Willie.

Willie says that Irene went into the Betts Creek Post Office to make a phone call. It must have been an old sign because Betts Creek was renamed Pentland in 1885.

In Darwin, the blackfellahs also took a close look at Willie and one of the women wept. Blond haired Bachhuber had no more reason to doubt his German background than Herr Keller from Peter Goldsworthy’s Maestro who lived above the front bar of ‘The Swan’ in the 1960s.

Had Gordon Buchanan any say in the matter, there would probably never have been a Darwin to Hall’s Creek leg of the Redex trials because (he notes in Packhorse and Waterhole) the establishment of Palmerston (Darwin) as the capital was an accident of history brought about by Charles Todd having followed McDouall Stuart’s route beyond the fifteenth parallel when mapping the Overland Telegraph route. It would have been better, Buchanan says, to have followed Stuart’s intended path to the Victoria River.

Irene adopts Scottish Presbyterian Don Watson’s implicit suggestion in The Bush that real Australia is much the same west of the Telegraph Line as east whereas her navigator takes a leaf from Irish Catholic Mary Durack’s Kings in Grass Castles.

Irene, Willie and Doctor Battery took the gravel road from Katherine to Hall’s Creek. Despite being desperate for sleep, Irene sped through Fitzroy Crossing and reached Broome in two shakes of a lamb’s tail (after dropping Doctor Battery off at Quamby Downs where he was the mechanic).

Quamby Downs station is a fair-minded person’s worst nighmare: whitefellah artefacts decay amid a melancholy atmosphere of neglect reminiscent of Patsy Durack’s ten-head battery rusting away up on the sandstone range at Halls Creek. Doctor Battery resents the station manager’s whitefellah chauvinism as much as had Charlie Flanigan in Kings in Grass Castles and puts up resistance at every turn. He would cheerfully have fixed the schoolteacher’s fridge, for instance, but not when ordered to do so by the overbearing manager.

The novel situates real Australia whitefellah dreaming at the junction with the indigenous verb to quamby – ‘to lay down, perchance to sleep.’ Irene Bobs slept but – preempting Kenneth Cook’s outback schoolteacher – woke in fright.

Carey’s fictional Quamby is located where the actual Quanbun station is. Camped nearby, marvelling at the star-studded firmament, I had something in common with Irene’s navigator. I have in my time, for, instance, roamed around arid country in a (grey engine) Holden and taken much from Jung’s Answer to Job. But they’re peripheral. It might have occurred anywhere but like Willie Bachhuber I had come to a fork in the road in the Kimberley and was aware of real Australia all around me. A Long Way From Home, that is to say, is actually about white Australia’s callous disregard for the way in which the first inhabitants have been pushed aside.

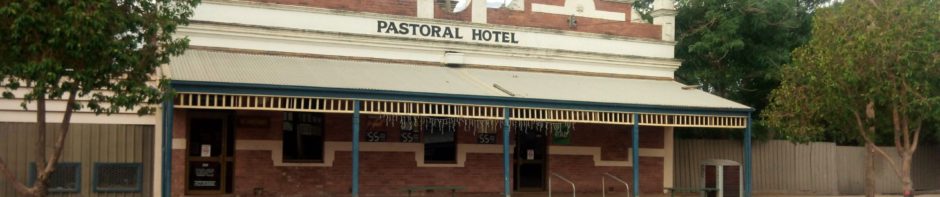

The Kimberley comes to a halt at Broome. I called to a Dampier Terrace pub and was struck by the degree to which the woman who pulled the beer was overdressed, even for a bar manager. Perhaps I should have noticed, sooner, that the waitresses were decked out in lingerie and exaggeratedly flouting their bums, breasts and crotches in all manner of ludicrous ‘come-ons’? Burlesque, yes; but this was like being an extra in a pointlessly crude video. Some of the women, those with cash tucked in their panties in the main, posed as if acting on instruction to be as silly as a wheel.

It turned out that I’d been in the Roebuck Bay Hotel where Willie Bachhuber had been taken aback by a priapic peacock. The type of hotel Drysdale used paint, Willie thought, increasingly ill at ease under the gaze of other patrons. He walked out into Sheba Alley and was even more disturbed by the effect his approach had on the Orientals who were there. He couldn’t read the signs.

Times change. The path where a forlorn Willie had wandered in 1954 – presumably a place where blokes went to find women like those moderns who tuck cash in their panties – is now the upmarket strip of Shiba Lane apartments.

Historical injustice

True history of the Kelly Gang

Penguin Books, copyright 2020

ISBN 978-1-76089-643-0

In 1980 I rented a friend’s house while she was ‘doing Europe’. When I subsequently sublet the spare bedroom to a couple of ‘outsiders’ the friend’s father began calling in to keep an eye on his daughter’s investment in the upmarket suburb. He soon realised the property was in good nick but was not so sanguine about the Ned Kelly transfer displayed in the bottom left-hand corner of the rear window of the couple’s panel van parked in his daughter’s driveway.

Recognising the inherent imbalance of power relations between landlord and tenant yet not one to tug the forelock, the driver of the vehicle parried by drawing comparison with the English legend of Dick Turpin. My friend’s father made no further face-to-face inspections and I made a mental note to read up on Ned Kelly.

One of those who takes a while to get ’round to it, on or about the fortieth anniversary of that exchange concerning the Holden window transfer I began reading Peter Carey’s novel about Edward Kelly and the gang. I’ve just finished the 478 page Booker Prize winner and have had my eyes opened. We did all that stuff about squatters at school but it taught me nothing other than that Australian History is boring.

Was.

As readers of my review of Carey’s A Long Way From Home will appreciate, the Travelling Write – a novel experience approach put everything in a new light. Mary Durack’s Kings in Grass Castles provided a springboard for greater appreciation of the Irish-Catholic community’s experience of the Selection Acts – an intriguing contrast with that of Don Watson’s as expressed in The Bush.

Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang takes up the relationship between Australia’s Irish-Catholic selectors and their Anglo-Protestant and Scottish-Presbyterian landlords – the powers-that-be, the squattocracy – and takes us deep into the heart of the devastating effect of institutional injustice born of the imbalance of power relations that carries on down the centuries. The quote from William Faulkner on the book-details facing page puts it in a nutshell: “The past is not dead. It is not even past.”